In November 1989, I was eighteen years old and happened to be working in Germany as an au pair. It was still West Germany then, and I lived in a small town called Uetersen not far from Hamburg, nowhere near the border with the East.

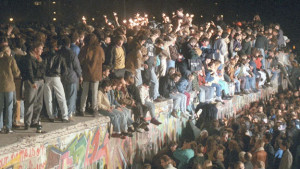

Today the world commemorates twenty five years since the East finally opened its borders in Berlin, a moment that came after months of protests and demonstrations against the Communist ruling forces in Eastern Europe. Despite this momentum for change, the night of 9th November still came as something of a surprise to everyone. To see people dancing on the wall, chipping away at it, families meeting for the first time in years – it was overwhelming. It was unbelievable.

Whilst I was nowhere near Berlin on that fateful night, I did experience some of the changes that took place in the country in the months that followed, and to celebrate this wonderful anniversary, I thought I’d share them with you.

I confess to being a very naive eighteen year old, and spectacularly dense at times, so I hope you will bear with me when my narrative is far from an incisive journalistic portrait of an historic global event.

The family I lived with were unusual in that they spoke very little English. This was good for me in some ways, because my A level standard German became fluent very quickly, but bad in the sense that in November, having arrived at the end of August, I was still terribly homesick. At that point I still hadn’t made any friends. I longed to hear my own language, and back then international phone calls cost a lot of money, so I only called home about once a week. I derived some comfort from travelling by train into Hamburg on my day off, browsing round the shops and visiting the Hamburg branch of The Body Shop, in order to buy such joys as banana conditioner. This felt like home.

I remember that particular weekend I had gone to Hamburg and on the train on the way back I found myself sitting opposite a man who I thought was a tourist. He was reading an English-language tourist map and looking anxiously out at every stop, in case he was going to miss his station. I wouldn’t normally have spoken to a stranger but it occurred to me that he might be a fellow Brit (deduced from the map, and the fact that he looked a bit dishevelled, which I seem to remember seemed like a British thing to be in 1989). So I asked: ‘Entschuldigung – sind Sie Engländer?’

He looked alarmed at having been addressed, replied ‘nein, nein’ and carried on looking out of the window.

After a few minutes, though, he began to talk to me. He told me that he’d come from the East, that he’d started travelling on the night the Wall came down, and he was journeying to see his sister who he hadn’t seen for nearly thirty years. She didn’t know he was on his way. He was excited and emotional and clearly, in hindsight, a bit shattered from travelling across what must have been a country he scarcely recognised as his own.

I believe I might have been a bit thrilled by this encounter but also a bit scared by this effusive, broken, overjoyed man. Many times over the years I have thought of him, wondered whether he found his sister and what passed between them that Saturday afternoon. I wish I had done more than wished him well (which I did manage to do, despite being 18 and a bit daft) – I wish I had somehow had the sense of being a part of something so personal, so global, and so intense.

My second memory is a bit less moving but nonetheless dramatic – this is the time I nearly got arrested at the East German border.

In the months that followed, there was free movement across the borders for German nationals, but other nationalities were still supposed to obtain a visa. I didn’t know this. (Did I mention I was a bit daft?) Anyway – in Germany at the time there was A Thing called, from memory, a Werbeverkaufsveranstaltung. These were effectively day trips that were advertised in the local paper, at a ridiculously low, practically free, price. The deal was that you got to go on a coach to some exciting destination – usually castles, historic cities, of which there are many – and on the way you would stop at a Raststätte (rest stop) somewhere and have a traditional cooked lunch, and afterwards for an hour or two they would put you in a room and sell you household tat. It was a way of selling things like teatowels and ironing board covers to retired people and housewives. Now from my point of view these things were great, I had very little money and it was a way of getting to see places. I was never bothered by the intensive sales pitch because a) I had no money anyway and b) they talked so fast and so colloquially once they got going (think marker trader) I couldn’t follow it anyway.

The person who introduced me to the Werbeverkaufsveranstaltung was the family’s cleaning lady, Frau Klinck (that was her real name). She was a slightly batty, slightly terrifying lady who was my only friend in Germany for a long time. She took me on a few of these things but I remember on this one occasion I decided to go on my own – to Schwerin, a beautiful city in the North East of Germany. I went on a coach with a load of pensioners, all of whom were complete strangers. When we got to the border (which was on the motorway), the coach parked up and the driver collected our passports. My British one was huge back then, the West German ones were small and there was mine on the bottom. A few minutes later an East German border guard got on and said ‘Wo ist die Engländerin?’ I put up my hand.

He came over to me and demanded to know why I hadn’t got a visa.

Well, you can imagine…. I said I didn’t know I needed one.

He got off the coach again and the pensioners all started whispering amongst themselves. The coach driver told them all to be quiet, because the border guards ‘could be Stasi’. I was picturing having to wait at the border for the day and hope that the coach would pick me up on the way back – that was the best case scenario. I couldn’t imagine this ending well.

After a while the guard came back and told me to get off the coach.

I went into an office with three men in uniform and they told me that they were prepared to issue me a visa there and then for the cost of DM30 (from memory this was about £10). This was quite literally all the money I had with me, but thankfully I had it and I handed it over. They put a fancy stamp (an actual postage stamp) in my passport and that was it, I was free to go. I went back to the coach on jelly legs and took my seat again, apologising to all the pensioners for the delay.

Once we were moving again I found myself crying in my seat because it had been bloody terrifying for a minute back there, and I could hear all the people on the bus still muttering about it. I had no money at all – not a pfennig – and while that wasn’t the end of the world I was cursing myself for not checking the border requirements for foreigners.

But, dear reader, this wasn’t the end of it. A few minutes later, the old chap in the seat behind me tapped me on the shoulder and handed me a sandwich bag full of money. For you, he said. The pensioners had had a whip round. I had about DM50 in a bag, much more than I’d started with. Needless to say their kindness was overwhelming, and like the man on the train, I’ve never forgotten them. (Learned a lot about karma, that day).

After that drama, I had a great day out in Schwerin, which was beautiful. I bought a book for 10 Marks (about DM3) called Berlin, Hier Bin Ich by Rudi Benzien. I still have it. Schwerin has a wonderful baroque castle on its own island. Here it is:

As the year progressed I finally found a local church that welcomed me in and I made some great friends from the youth group. I went to Berlin with them to see Billy Graham speak at the Brandenburg Gate, and on one occasion I went into East Berlin with my friends to see a Great Aunt of theirs. This was an experience like no other. East Berlin was like time had frozen in the 1950s – but everything had faded behind a blueish haze of exhaust fumes from the ever-present Trabis.

At some point during that visit I went into a cafe in Unter den Linden (the main thoroughfare leading up to the Brandenburg Gate, back then still behind the wall) and met Kate Adie in there. I got her to sign a postcard for me.

Somewhere in this house I have photos of me chipping away at the Berlin Wall, said small chunks of the Berlin Wall, and a postcard with Kate Adie’s signature on the back. All of these, together with other precious things, are somewhere in a Safe Place… so, much as I would like to illustrate this post extensively with proof that I was there, this testimony is all that I have.

With love and respect to the people of Germany, who made me very welcome, and helped me become an adult.

That was incredibly moving, Elizabeth – thank you so much for sharing it. Damp eyes as a result 🙂 xx

This is wonderful, could have been next to you listening, so interesting such great memories

What a fascinating insight. Thank you, Elizabeth. We have a little piece of the Berlin Wall in a bottle. It belonged to my Dad. Although he’d never been to Germany, himself, he appreciated the importance of the wall coming down, and treasured his little piece of it.

Wonderful story.

Travelling through East Germany was certainly nerve racking. I went on a train from Hamburg to Berlin – in transit across a chunk of East Germany. So rattled I didn’t even grasp that the guards were speaking English!