I watched Amber, the crime drama created by RTE in Ireland and shown recently on BBC Four, entirely on BBC iPlayer, anxiously avoiding spoilers because I was determined not to find out what happened to the 14-year-old who went missing in episode one.

I had a particular interest in this one because it occurred to me that the storyline was along the lines of the plot I’m writing about in my next book, Behind Closed Doors (which will be coming out in paperback next year). I’m always anxious about unintentionally absorbing other people’s plots, but also I find the mystery attached to missing people fascinating. In the UK around 900 people go missing every day, according to this article in the Guardian, and many of them are never found. Of course, a proportion of these people, as in the article, are intentionally leaving old lives behind and beginning a new life anonymously elsewhere, rather than something sinister happening to them.

That, in itself, is interesting, because closing down one life and starting another one isn’t an easy one to do. In my early twenties, someone paid some money into my bank account that I didn’t want. You’d think it would be a simple matter to return it, and request that such a thing doesn’t happen again, wouldn’t you? Not at all. In the end, I had to close down that account and change my bank completely, losing my credit history in the process, because any future unwanted deposits would just have followed me to a new account with the original bank. And that was just a small administrative headache. Imagine having to find a new home, a new job, bank, phone, utilities, passport, council tax, all without reference to your old life? How much do you want to disappear?

Then, of course, there is the question of those who haven’t done this on purpose; those with apparently happy lives, no reason to go, and children. What happened to them? Discounting the possibility of aliens, or something supernatural, these people have gone somewhere. A whole planeful of people recently have ended up somewhere. The not knowing, for a bystander like me, is engrossing enough, how it must feel to have had a loved one disappear without trace must be absolutely unbearable.

Which brings me back to the subject of Amber.

The brief description on the BBC website proclaims it is a crime drama ‘in which the disappearance of a 14-year-old girl sparks a two-year search and intense media spotlight on her family’.

Now I’m possibly going to give away a spoiler here, so brace yourselves, but it’s a bit of an anti-spoiler. Because there aren’t any spoilers.

YOU DON’T GET TO FIND OUT WHAT HAPPENED TO AMBER.

At the end of episode four, I was so convinced there must be more of the story to come, I searched the web to see if it really was ‘episode 4 of 4’ or if there was a second series underway. That’s how I found the media reviews criticising the lack of an ending, and the producers’ explanations that this lack of a resolution is entirely deliberate:

I can appreciate the desire to do something a bit different, and hats off to them for trying, but I think they went about it all wrong. For a start, this is billed as a crime drama, not as an exploration of what happens to the family that’s left behind when a child disappears. Secondly, the structure of the piece – beginning with ‘Day 1’ and thereafter flipping backwards and forwards between ‘Day 1’ (bits of which featured in every episode) and ‘Day 570’ with many, many other days in between, kind of implied that there would be a ‘Day X’ when Amber would return, or be found.

Thirdly, and most importantly, the viewer got to see things that happened to Amber after her Dad dropped her off at a friend’s house. She didn’t go inside. After that, the police had some CCTV footage of her at a train station and sitting on a train. She got off a stop early. That was it, for Amber, as far as the official investigation went.

But we got to see lots more of Amber. We saw her meeting up with her mysterious ‘Manga Boy’ online friend. We got to see her buying a replacement UV lamp in a shop. We saw her bumping in to a ruffian (who we also know sparked off a whole load of red herrings) who stole her mobile phone – which caused an illegal immigrant to be deported back to China for being kind and trying to return the phone to her family – and eventually, frustratingly, ended up being dropped down a drain by a toddler.

We saw Amber happily wandering around town for no apparent reason other than that she didn’t fancy having lunch with her gran. Finally we saw her getting off the train a stop early having discovered her phone missing, and wandering off down a wooded lane.

In the mean time, I (and presumably the other viewers), were busy working our way through the possible suspects: the man on the beach, who’d asked Amber about her phone on the day she went missing? Her slightly strange younger brother, effectively ignored by his rowing parents after his sister went? The odd looking bloke on the train? Manga Boy? The white van man who pulled up behind Amber as she walked along the woodland road – and then drove off again? Or the creepy guy who’d been in prison when Amber went missing, and appeared to know more about her than was possible? Oh, but he knew the ruffian who stole Amber’s phone – so that explains that one. And then of course, you have Amber’s Dad’s business partner, who is carrying on a secretive relationship with Amber’s mother’s best friend – following all that? Why the secrecy? And then there’s Amber’s Dad himself, who suddenly in the final episodes starts pursuing footage of child abuse on the web in the hope of finding images of his daughter. Right.

My point with all of this, is that Amber LOOKED like a crime drama. Red herrings were scattered liberally. The jumping back and forth between the days of Amber’s absence suggested that clues were being revealed. And the fact that we got to see extra bits of Amber after the CCTV, after her Dad waved her off: ‘in real life you don’t get answers’, says Paul Duane.

In real life you don’t get to see more of the missing girl’s last day, either.

I think the key is that, as Paul Duane adds casually, at one point they ‘thought she’d be in somebody’s cellar’ – they clearly were working towards a traditional crime drama with a resolution, and then at some point they changed their minds. By the look of it, when most of the filming had already been done. I am hoping that they might reconsider, and work up a second series which answers all of the many questions so temptingly posed in these four episodes. Cellar or no cellar.

Oh, so frustrating! I feel cheated by it.

By contrast, the BBC’s other recent offering, Happy Valley, was so excellent I’m still thinking about it weeks later. Now that’s how to do a crime drama….

As a little aside, my procrastination device of choice recently has been collecting inspirational quotes on Pinterest. You will therefore note that this blog post is liberally sprinkled with them. Not all, strictly speaking, relevant. Enjoy.

As a little aside, my procrastination device of choice recently has been collecting inspirational quotes on Pinterest. You will therefore note that this blog post is liberally sprinkled with them. Not all, strictly speaking, relevant. Enjoy.

Added to which, the fact that our books followed a similar trajectory did me no harm at all, quite the reverse in fact: I’m fairly sure Into the Darkest Corner got a substantial amount of sales from the ‘if you liked this, try…’ recommendations. Whatever glory the other book had, some of it reflected on Into the Darkest Corner, and so me wishing it away was beyond idiotic.

Added to which, the fact that our books followed a similar trajectory did me no harm at all, quite the reverse in fact: I’m fairly sure Into the Darkest Corner got a substantial amount of sales from the ‘if you liked this, try…’ recommendations. Whatever glory the other book had, some of it reflected on Into the Darkest Corner, and so me wishing it away was beyond idiotic. That’s the nature of writing, and to paraphrase Helen’s article – wait for it, this is genius – writing isn’t a competitive sport. It’s art, and as a result the ‘best’ is entirely subjective. The best piece of writing won’t always (or maybe even ever) win, because if you think about it there is no such thing. My best book isn’t any ‘better’ than your best book. Comfortingly, it isn’t any worse either. It’s just different.

That’s the nature of writing, and to paraphrase Helen’s article – wait for it, this is genius – writing isn’t a competitive sport. It’s art, and as a result the ‘best’ is entirely subjective. The best piece of writing won’t always (or maybe even ever) win, because if you think about it there is no such thing. My best book isn’t any ‘better’ than your best book. Comfortingly, it isn’t any worse either. It’s just different. But the results of my writerly obsession were horrible. What’s the point in writing, when someone’s always going to be better than you? Someone’s always going to sell more books, have more public exposure, get more TV and film deals, earn more money, have more followers on Twitter, be thinner and more gorgeous, and whatever else you personally use to define what success looks like. Comparing yourself to anyone else in an artistic field is completely and utterly futile. You can’t win, because there aren’t any real, qualified, time-checked and verified winners in this particular challenge. You just end up hating yourself and feeling inadequate.

But the results of my writerly obsession were horrible. What’s the point in writing, when someone’s always going to be better than you? Someone’s always going to sell more books, have more public exposure, get more TV and film deals, earn more money, have more followers on Twitter, be thinner and more gorgeous, and whatever else you personally use to define what success looks like. Comparing yourself to anyone else in an artistic field is completely and utterly futile. You can’t win, because there aren’t any real, qualified, time-checked and verified winners in this particular challenge. You just end up hating yourself and feeling inadequate. 2. The person you’re searingly jealous of is quite possibly riddled with insecurities and doubts, just as you are. And someone is quite possibly burning up with envy because they believe you’re better than they are, right at this very minute. It’s not a good thing, though. Feel sad for them, because their feelings are holding them back in the same way yours are!

2. The person you’re searingly jealous of is quite possibly riddled with insecurities and doubts, just as you are. And someone is quite possibly burning up with envy because they believe you’re better than they are, right at this very minute. It’s not a good thing, though. Feel sad for them, because their feelings are holding them back in the same way yours are!

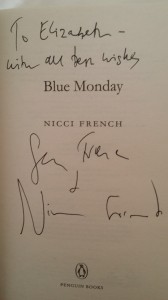

One of the must-see panels for me was about writing in partnership, and featured Nicci Gerrard and Sean French, who write together as Nicci French, and Alexander Ahndoril and Alexandra Coelho, who write as Lars Kepler. As you may know or have suspected, I am a massive fan of Nicci French. The early books had a big influence on me.

One of the must-see panels for me was about writing in partnership, and featured Nicci Gerrard and Sean French, who write together as Nicci French, and Alexander Ahndoril and Alexandra Coelho, who write as Lars Kepler. As you may know or have suspected, I am a massive fan of Nicci French. The early books had a big influence on me.

The panel was chaired by

The panel was chaired by